|

God's Triune Existence |

| Yes! It Could Be Today! |

| HOME :: Theology Studies :: Theology :: Trinity :: |

Before concluding this section on God’s triune existence, there are some related subjects that should be addressed. We will consider four.

First, there is a clarification that is needed regarding perspectives on the Trinity. How we think about the triune God must be “adjusted” depending on where we are in the outworking of his plan. Over time, two things about God have changed. One is a vocational change. The other is an ontological change. It will be helpful to think about these changes.

The second subject involves the person-to-person relationships within the Trinity. How do the three persons relate to one another? Closely related to this subject is that of the designations for the persons of the Trinity. How are they identified? And, what is the significance of these designations?

Thirdly, we will consider the Hypostatic Union. This union involves the addition of a human nature to the person of the Son so that the Son individualizes both a divine nature and a human nature. At this point the subject of this union is introduced so that we might see how it relates to the structure of the Trinity itself. We will develop it further when we consider God’s vocational existence.

And fourth, we will consider illustrations of the Trinity. Do illustrations really help us understand this doctrine? Can we find examples from what we know about creation and use them to illustrate the Trinity in any meaningful way? Even if we could, would understanding an impersonal illustration really help us understand a personal being?

As we read in Scripture of God’s working, it becomes apparent that what God is doing now accords with a plan he has made in the past. God is doing what he determined he would do. In Acts 4 the disciples expressed their confidence that the events they were witnessing were fulfillment of God’s plan. Even sinful men were accomplishing “whatever [God’s] hand and [God’s] plan had predestined to take place” (4:28). God has determined beforehand that certain events would take place. These events take place as God’s plan unfolds.

It seems that as we reflect on what God has done in fulfilling his plan, we need to recognize the significance of two important milestones. The first milestone[1] occurs at the point where, having made a plan[2] or decree, God begins to implement that plan. This milestone is vocational[3] in nature. It marks the beginning of God’s vocational activity. The second milestone occurs at the point where the Son becomes incarnate. At that time added to the person of the Son is a human nature. This milestone is ontological[4] in nature even though it involves fulfillment of God’s vocational plan.

Given these milestones, it may be helpful to reflect on the Trinity, and particularly the three persons of the Trinity, in relation to them. These milestones distinguish “periods” in the “history” of God to the extent that he has revealed himself to us. Regarding the vocational milestone, we can think of “pre-Plan” and “post-Plan” periods where the line of demarcation is the outset of the plan’s implementation. With regard to the ontological milestone, we can think of “pre-Incarnation” and “post-Incarnation” periods where the line of demarcation is the Son’s taking on of a human nature. This understanding permits us to divide a timeline of history into three periods. There is a “pre-Plan” period, a “post-Plan/pre-Incarnation” period, and a “post-Plan/post-Incarnation” period.[5] From time-to-time going forward it may be help to notice these periods.

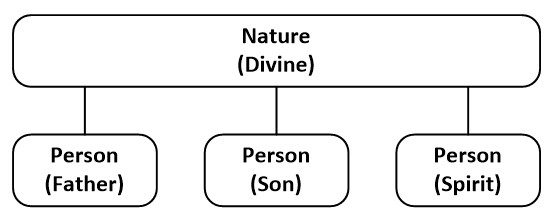

Up to this point we have been concerned with understanding the “structure” of the Trinity and as such have focused on the person-to-nature relationships that exist. Each of the three distinct persons shares the one divine nature. Figure 1 is a diagram showing the person-to-nature relationships in the Trinity.

Figure 1: The One Divine Nature and Three Distinct Persons

Before moving on we want to pause to reflect on person-to-person relationships within the Trinity. These relationships consider how the three persons relate to each other. There are two specific person-to-person relationships which we wish to address, the one which is ontological and the other which is vocational.

It is important that these two perspectives should be recognized and kept distinct. If they are not, confusion will result because of seeming contradictions found in the statements of Scripture. These two perspectives should be kept in mind when viewing both the Trinity itself and, as we will see, the designations used to identify the members of the Trinity.

We will first consider the person-to-person relationships as the three persons relate to one another ontologically. We will then move on to look at these relationships when viewed vocationally. At this point the intent is simply to point out distinctions in perspective. These distinctions will be fleshed out in the two subsequent sections which are specifically related to these relationships.

When we are considering the three persons ontologically, we are considering them as they exist inherently, in and of themselves. Herein the term “ontological” refers to the Godhead as it exists. Frame writes, “The ontological Trinity … is the Trinity as it exists necessarily and eternally, apart from creation. It is … what God necessarily is.”[6] Since I believe that the Trinity has changed ontologically, I would simply say, “The ontological Trinity is the Trinity as it existed from eternity.” This is the trinity shown in Figure 1 above.

From this perspective the persons in the Godhead are equal in every sense of the word. “With respect to the essence of God, the three persons are equal to each other. Another way to say this is that the three persons are ontologically (with respect to their being or essence) equal to each other.”[7] They equally share the one divine nature and thus, by any measure, equally share any attribute or ability which that nature provides to them as persons. Thus, any characteristic true of one person will be true of the other two as well. Furthermore, there is no subordination in the Trinity as it exists ontologically. If we were to diagram the ontological relationship of the three persons of the Godhead among themselves, we might present it as in the following “horizontal” diagram.

![]()

Figure 2: Ontological Relationship of the Three Persons

A later section of this study, “God’s Ontological Existence,” will look at the persons of the Godhead from this “as they exist” perspective.

Before moving on to consider the vocational relationships, perhaps a comment is in order regarding the designations Father, Son, and Spirit. These are the designations that we typically use to refer to the persons who are God. These are asymmetric designations not reflective of the complete equality of the three persons.[8] So these are not ontological designations. These are vocational designations, in a sense reflective of roles of the three persons.[9] As such these names do not reflect the equality present in the Trinity when viewed ontologically.[10] Other designations used to distinguish the persons, such as First, Second, and Third, are not helpful in the sense that they might imply an ordering among the persons where there is no ordering. At this point in time God has not chosen to reveal any names the persons might use to refer to themselves apart from those associated with their vocational work.

When we are considering the three persons vocationally, we are considering them as they work. This second perspective considers the Godhead as the persons have decided to work together to accomplish an agreed upon plan. The plan to which I am referring is the one that involves the creation of the universe, angels, and man and includes Satan’s rebellion and man’s fall and the salvation of man, all for God’s glory.

Addressing this perspective of the Trinity Frame writes, “The economic Trinity is the Trinity in its relation to creation, providence, and redemption. These are roles that the persons of the Trinity have freely entered into; they are not necessary to their being.”[11] As he points out, this view of the Trinity sees the three persons as they freely work.

Regarding the independent functioning of the members of the Godhead, Erickson writes,

The function of one member of the Trinity may for a time be subordinate to one or both of the other members, but that does not mean he is in any way inferior in essence. Each of the three persons of the Trinity has had, for a period of time, a particular function unique to himself. This is to be understood as a temporary role for the purpose of accomplishing a given end, not a change in status or essence.[12]

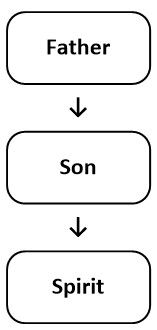

Our understanding of the vocational person-to-person relationship is based on God’s revelation of his arrangements as he works to carry out his decisions. From this perspective we see an ordering of the members, Father over Son over Spirit. The Son is subordinate to the Father; the Spirit is subordinate to the Father and the Son. These are relationships that commenced at the outset of the “post-Plan/pre-Incarnation” period and continue forward.[13]

These personal vocational relationships can be seen in the following “vertical” diagram.

Figure 3: Vocational Relationship of the Three Persons

A later section of this study, “God’s Vocational Existence,” will look at the persons of the Godhead from this perspective.

It must be remembered that this ordering is based on God’s revelation to us and is indicative of the plan that he is executing that includes us. The fact that the members of the Godhead have agreed to work together in the plan we see them does not mean that other plans have not existed in the past, do not now presently exist, nor will not ever exist in the future. God is at liberty to do anything he chooses and at any time, but within limits. Those limitations are the ones God has placed upon himself by virtue of any arrangements or commitments made in the plan about which we know or any other plans unknown to us. For example, the person of the Godhead we know as the Son now has two natures, one divine and one human. That will everlastingly be the case. And if the Godhead has worked, is working, or will work with respect to other plans, there is no reason to assume that the relationships seen with respect to the plan we know are uniformly the same in others. Ontologically there is no inherent ordering of the persons of the Godhead. Any vocational orderings are voluntary by agreement.

When considering the relationship among the three persons of the Godhead, two related subjects come into focus: the eternal generation of the Son by the Father and the eternal procession of the Spirit from the Father and Son. Regarding these two subjects, the Westminster Confession of Faith includes the following statement.

In the unity of the Godhead there be three persons, of one substance, power, and eternity; God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Ghost. The Father is of none, neither begotten, nor proceeding; the Son is eternally begotten of the Father; the Holy Ghost eternally proceeding from the Father and the Son.[14]

Interestingly, these two doctrines have created difficulties for those who espouse them and who also hold to full equality of the three persons in the Trinity. Early in the history of the doctrine of the Trinity writers worked to defend both positions as true. And that effort continues today.[15]

Because these two doctrines (generation and procession) have a long history in the teaching of the Church and they relate to the Trinity they should be addressed. It is the conclusion herein that neither eternal generation nor eternal procession is an ontological reality. I believe that neither doctrine can be derived from Scripture. As Frame writes, “The best arguments for eternal generation and procession are based on analogy, rather than explicit biblical teaching or logical inference from explicit teaching.”[16] It is true that Scripture does speak of the begetting of the Son by the Father and of the proceeding of the Spirit from the Father (being sent by the Son). However, it seems best to see that both actions relate to God’s vocational activity and, as such, they are not eternal. These two relationships do not describe how the Godhead exists ontologically.

First, we will consider the doctrine of the eternal generation of the Son by the Father. For a definition we will use that provided by A. A. Hodge and referenced by Loraine Boettner and others.

The eternal generation of the Son is commonly defined to be an eternal personal act of the Father, wherein, by necessity of nature, not by choice of will, he generates the person (not the essence) of the Son, by communicating to him the whole indivisible substance of the Godhead, without division, alienation, or change, so that the Son is the express image of his Father’s person, and eternally continues, not from the Father, but in the Father, and the Father in the Son.[17]

This doctrine teaches that the existence of the person of the Son is in some way due to a work of the Father and that this work of the Father is “by necessity of nature, not by choice of will,” thus eternal. The result is that “the Son is the express image of his Father’s person.” If we assume that the word translated begotten, monogēnes, is derived from the verb for born, gennō, then Scripture does say that God the Father has begotten the Son. He is “the only begotten from the Father” (John 1:14, NASB). However, where is there scriptural evidence that this is an eternal begetting or even that this begetting is ontological? It may well be vocational. Scripture says nothing about “an eternal personal act” that the Father “by necessity of nature” undertakes. After citing several references typically used to support this doctrine, Boettner writes, “The present writer feels constrained to say, however, that in his opinion the verses quoted do not teach the doctrine in question.”[18] I would concur. Frame questions, “Can we … speak of an ontological begetting, an eternal generation, to which [the Son] owes his eternal sonship?”[19] He then continues, “Many have dismissed this question (and the answers to it) as speculative, and there is some truth in this criticism.”[20]

I think a better understanding of the begetting of the Son by the Father is to see it as vocational, not ontological. This begetting, or placing, of a person of the Trinity into the role of a son (at the same time placing another person into the role of a father), seems to best accord with Scripture. Thus, as equals in the Godhead two of the persons assumed the roles of Father and Son and did so voluntarily. There is no “necessity of nature” here. This “begetting” took place “by choice of will.” By this view, the Father and Son took on their respective roles and responsibilities as the plan or decree of the Godhead was being implemented. Thus, this relationship is not eternal. Regarding this issue of Sonship, see the article “Decretal Sonship.”

Having considered eternal generation, we now move on to the Spirit’s eternal procession from the Father and Son. Again, for reference, we will use the definition provided by A.A. Hodge.

Theologians intend by this phrase [Procession of the Holy Ghost] to designate the relation which the third person sustains to the first and second, wherein by an eternal and necessary, i.e., not voluntary, act of the Father and Son, their whole identical divine essence, without alienation, division, or change, is communicated to the Holy Ghost.”[21]

This doctrine of the eternal procession of the Spirit is difficult to defend from Scripture. This doctrine, to some degree, is necessitated by the doctrine of the eternal generation of the Son. It would seem difficult to hold the former without also holding the latter. Essentially, procession must be the same action as begetting, although in the case of the Spirit two persons are involved rather than one. As Frame notes, “many theologians have expressed ignorance as to how procession differs from generation.”[22] The passage usually put forth in support of this doctrine is John 15:26. John cites Jesus as saying that he would send the Comforter, the Spirit of truth, who would proceed from the Father. But this statement, at least regarding Jesus’s part of sending, was referencing a still future event; he said that the Spirit is the one “whom I will send to you from the Father.” There is not a hint of anything eternal. Even if one accepts “who proceeds from the Father” as a historical reality, then, as with the begetting of the Son, the better understanding is to view this as vocational rather than ontological. Proceeding from the Father may indicate no more than the fact that the Spirit was at that time in the presence of the Father and would come to earth from there.

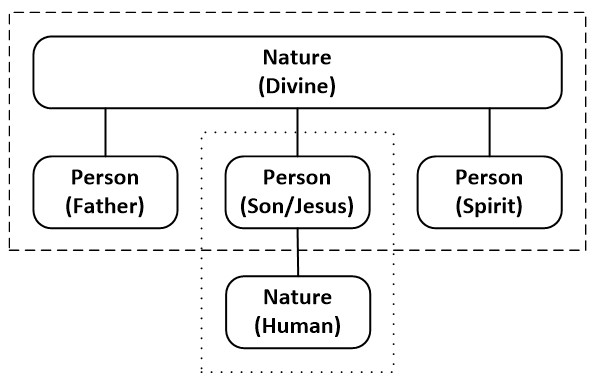

Up to this point the focus has been on the persons and nature of the Godhead. We now turn to the subject of the Hypostatic Union, a union initiated at the time of the Son’s Incarnation. The discussion of this union is technically not germane to a consideration of the triunity of the Godhead itself. However, this union does involve a basic ontological change in the existence of the triune God. At the Incarnation a change was introduced into the structure of the Godhead such that the Son from that point forward individualized two distinct natures, one divine and one human.[23]

Prior to the Incarnation the three persons in the Godhead each individualized the single divine nature. However, since the Incarnation, one of those persons, the Son, has also individualized an additional, a second nature, specifically, a human nature. At the Incarnation the second person of the Trinity took upon himself humanity. This taking on of humanity involved a union of God and Man, divine nature and human nature, via the person of the Son. As such it has historically been designated the “Hypostatic Union.”[24] In this Hypostatic Union the nature of deity and the nature of humanity have been “joined together”[25] via a single person. The person, specifically the preexisting person designated as the Son, provides the individualization for these two natures. The Son, and the Son alone, gives individuality to two distinct natures, one divine and one human.

Thus, a few comments about this union and how it relates to our understanding of person are in order. Later, we will consider the evidence that such a union exists. For now, we will just assume that at the time of the Incarnation the Son started individualizing a human nature while at the same time he continued individualizing his divine nature. Thus, the Son, since the Incarnation also known as Jesus, as a person presently gives individuality to two distinct natures, one divine and one human. In this regard we can say the Son, unlike the Father or Spirit, is fully God and fully Man.

The following diagram shows the Trinity with a human nature joined to the Son’s person. It is the current state of the Godhead, the being God. The Son is also Jesus. Thus, this person is fully divine and fully human at the same time. How this is possible and how it works is a mystery, perhaps the deepest mystery yet revealed to man.

Figure 4: The Hypostatic Union

In this diagram, the dashed box shows the triune Godhead as it existed prior to the Incarnation, before the Son added a human nature. From eternity the three, distinct persons had been individualizing one, divine nature. This has already been explained. The addition of the human nature individualized by the Son illustrates what took place at the time of the Incarnation. The dotted box shows the eternally existing person of the Son individualizing a human nature as a result of the Incarnation. It should be remembered that the designation Jesus for the second person of the Trinity is a designation that originated at the time of the Incarnation, when this person added a human nature.

Going forward we will make a distinction between God’s pre-Incarnation existence and his post-Incarnation existence even though both consider God as he exists. Pre-Incarnation existence will focus on God as he has existed from eternity apart from creation. Post-Incarnation existence will focus on God as he now exists because of creation and particularly because of the Incarnation. Since this Hypostatic Union is not eternal, it is more properly a part of a consideration of God’s vocational existence. However, the addition of a human nature to the person of the Son does represent an essential, in the sense of ontological, change in the being of the triune Godhead. While the Trinity itself did not change in the sense that three distinct persons are sharing one divine nature, the Godhead itself is ontologically different now than it was prior to the Incarnation.[26]

This union reflects how the Godhead has been changed by what God has chosen to do vocationally. From a diagrammatic perspective, Figure 1 represents the pre-Incarnation perspective and Figure 4 the post-Incarnation perspective. Both perspectives represent what is ontologically true. Figure 1 illustrates the “from everlasting” being of the Godhead prior to the Incarnation. Figure 4 illustrates the “to everlasting” being of the Godhead subsequent to the Incarnation. The Incarnation thus has incredible significance regarding existence of the Godhead.

Over the years there have been many attempts to provide illustrations or analogies for the Trinity. They have been offered to help us comprehend God’s triunity. It has been hoped that such illustrations would aid our understanding of this difficult concept. These illustrations have been derived from the natural order in an attempt to take something with which we are familiar and use it to help us understand something that is not familiar. These analogies are usually triads of some type. Frame in his volume The Doctrine of God lists over 100 examples of triads, “including many that might be thought to reflect the Trinity in one way or another.”[27] While triads may reflect to some degree the threeness of the Trinity, as actual illustrations of the Trinity itself all triad illustrations fail.

There are two basic problems with these triad illustrations. First, there are problems with illustrations which include an “or” relationship. One example used is that of a molecule of water. Because water can be found in three familiar states this is proposed as an illustration of the trinity. The state of a molecule of water is solid or liquid or gas. Thus, supposedly, in some sense water represents God’s triunity. However, at any given instant a molecule of water can be in only one of these states. That is like saying that God is Father or Son or Spirit, but only one at a time. The illustration of time being past or present or future has the same problem. Any point in time that we reference can only be in one of these states. And a point of time in the past can never again be present or future. Such analogies are not reflective of God’s triunity.

Second, there are problems with illustrations which include a “consists of” or “is composed of” or the like kind of relationship. One example used is that of an egg. An egg is composed of a shell and a white and a yolk. But to say this is an illustration of the Trinity is to say the Trinity is composed of the Father and the Son and the Spirit. This simply is not the case. Nothing in the illustration accounts for the divine nature that the three persons share. The nature is different than the persons. The illustration of space consisting of length and width and depth is no better. In these analogies the three “make up” or “add up to” the one. Not so with the Trinity. It is not true that three persons make one God or that God consists of three persons. There is more to God’s being than just the three persons. There is also the nature that these three persons share, the nature which makes the three person God.

Does this mean that these illustrations have no value? Note the following observation from MacArthur and Mayhew.

No illustration can fully communicate the Trinity. … But as long as teachers make clear that every analogy will be to some extent inadequate, it may still be profitable to use these improper illustrations [emphasis added] to explain why and how they fall short as adequate representations of the Trinity. By understanding that the Trinity is not like the three states of H2O (ice, water, vapor), the student learns to reject modalism. By learning that the Trinity is not like the three leaves of a single clover, he eschews partialism. By grasping that the Trinity is not like light and heat emanating from the sun, he disclaims Arianism.[28]

So then, if we understand that these triads are incomplete and do not accurately depict the Trinity, perhaps they may serve some purpose.

In the end, these triad illustrations fail because there are four components that must be accounted for when considering the Trinity, not just three. There are the three persons and there is the one nature. The Trinity consists of Father and Son and Spirit, the persons, and divinity, the nature. As Erickson observes, “Most analogies drawn from the physical realm tend to be either tritheistic or modalistic.”[29] Any illustration of the Trinity must take into consideration the distinction between persons and nature and account for both. If it does not, it only clouds the issue.

As an example of a possible illustration, let me offer the following. However, let me offer it with a disclaimer. It is offered only to show a contrast with triad illustrations. I do not say that it is a good illustration in any sense of the word. I do not think a good illustration exists. An illustration of the Trinity that accounts for both the persons and the nature must include three things of one kind or class and one thing of another kind or class with that one in some sense giving its nature to the other three. This is not a simple task. So then, consider a lowly vegetarian pizza pie that has three toppings. On such a pizza there are three toppings, say mushrooms and onions and peppers, and there is one pie (the basic pizza crust with sauce and cheese) on which the toppings sit. The toppings are distinct from each other. And the pie, perhaps we could say, gives its nature to the three toppings which share it. In this example the vegetarian pizza is an entity consisting of three toppings sharing one pie. Similarly, God is a being consisting of three persons sharing one nature. Again, this is not a good illustration. But hopefully, as intended, it does help demonstrate the contrast with simple triad illustrations.

Other ways of illustrating or clarifying the concept of the Trinity have also been attempted. In Erickson’s discussion of analogies, he points out that “some theologians … have intentionally utilized grammatical ‘category transgressions’ or ‘logically odd qualifiers’ to point out the tension between the oneness and threeness.”[30] He uses “God are one” and “they is three” as examples. To some degree we find this same tension in Scripture. In instances where we find God speaking about himself (or perhaps themselves) we find plurals used. “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness” (Gen 1:26). Moses immediately follows this declaration with singular references to God. “So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him, male and female he created them” (Gen 1:27). This tension at times leads to difficulties in understanding Scripture, particularly with the word God. Sometimes the word God refers to a particular person in the Trinity. At other times we understand it to refer to all three persons or to the entire being of God. Context helps us decide. For example, note Romans 1:9, “God is my witness, whom I serve with my spirit in the gospel of his Son.” The reference to “his Son” helps us see that Paul is using God here as a reference to the Father. Romans 8:28 and its context provide a similar example. James 2:19 provides an example of where the word God is a reference to the entire Godhead. James wrote, “You believe that God is one.” So, no doubt, the fact that God is triune (and we humans are not) does from time to time present us with some language inconsistencies.

[1] There appears to be a milestone that is prior to this “first” one. That would be the milestone where the persons of the Godhead decided to make a plan for their own glory, a plan which they would then carry out. Unlike the two milestones to be considered, this milestone has no effect on the Godhead ontologically or vocationally.

[2] There are many who understand the plan of God to be eternal. Given the terminology used in Scripture with reference to this plan, I think this not the case. See the articles on God’s vocational existence.

[3] By “vocational” I am referring to God as he works.

[4] By “ontological” I am referring to God as he exists.

[5] I think that the plan being presently implemented will, upon completion, be followed by a subsequent plan. Of course, any subsequent plan will take into consideration any commitments made by God in the present plan.

[6] John Frame, The Doctrine of God, p. 706.

[7] MacArthur and Mayhew (eds.), Biblical Doctrine, p. 191.

[8] Below I will consider the Father’s begetting of the Son and the procession of the Spirit from the Father and Son.

[9] See further in the study “Decretal Sonship.”

[10] It seems best to see their intra-Trinity relationships as persons to be of a brother-to-brother character.

[11] John Frame, The Doctrine of God, p. 706.

[12] Erickson, Christian Theology, 2nd edition, p. 363.

[13] In saying that these relationships “continue forward” I do not mean that they necessarily continue forever. Since these are vocational relationships, in another future plan the relationships could change.

[14] WCF 2:3, cited from BibleWorks.

[15] See, e.g., Trinity Without Hierarchy, Bird and Harrower (eds.). The subtitle of the work is “Reclaiming Nicene Orthodoxy in Evangelical Theology.”

[16] John Frame, The Doctrine of God, p. 719.

[17] A. A. Hodge, Outlines of Theology, (London, T. Nelson and Sons, 1877), p. 149.

[18] Boettner, Studies in Theology, p. 121.

[19] John Frame, The Doctrine of God, p. 707.

[20] Ibid. (p.707)

[21] A. A. Hodge, Outlines of Theology, (London, T. Nelson and Sons, 1877), p. 158.

[22] John Frame, The Doctrine of God, p. 714.

[23] This change in the Godhead did not impact the nature of God’s being. The change was personal and it only involved one of the three persons of the Godhead, the Son.

[24] The Greek word hypostasis has been used historically to refer to the persons of the Trinity. This union is a person-based union.

[25] In saying “joined together” we are not saying the natures themselves are joined, but that the divine nature and the human nature are joined in the sense that one person possesses (individualizes) both kinds of nature. The natures themselves should not be viewed as comingled in any way. They should be seen as completely distinct.

[26] This truth must be reflected in our understanding of God’s unchangeableness.

[27] John Frame, The Doctrine of God, p. 729. The triads to which he refers are found in Appendix A, “More Triads,” p. 743.

[28] MacArthur and Mayhew, Biblical Doctrine, p. 193.

[29] Millard Erickson, Christian Theology, 2nd Edition, p. 364.

[30] Millard Erickson, Christian Theology, 2nd Edition, p. 364.